My Parkinson Story is a weekly column featuring member of our community, sharing their stories with PD. We are interested in sharing a wide array of experiences, including yours! PD looks different in everyone, and affects everyone differently, including friends and family of those with PD. If you’d like to share your story on our blog, please email us.

My Father was my Hero; He was also a Trauma Warrior

reposted with permission from Tristate Trauma Network

Friends, Colleagues, & Community Members, this is going to be a hard one for me to get through without crying a little, and that’s okay. No need to worry. I’m fully accepting of the sorrow and the grief I still feel after 7 years. I want to tell my father’s story and the part of it that is my story. I need to tell it. It’s been inside me for so long, and I’ve shared pieces, but it has evolved. I come to a greater understanding of it all the time, through the people I meet in this work, through hearing their struggles and their stories of hope, by telling pieces of my dad’s story and hearing people’s reactions to it, through learning new things about trauma and about myself. These things cause more of the tiny little lights strung across the darkness to turn on and help me to see things more clearly.

My father, William Wambaugh, lived a life of service to others. When some were dodging and protesting the Vietnam War draft, he happily answered the call. His father had gone before him and it’s what you do when you’re an able-bodied citizen needed by the country for protection. So he spent some time in the de-militarized zone of Korea as his Vietnam War service. He didn’t mean to go to Korea, but his baggage was lost and he was sent out later than the rest of his army unit, which meant a different flight and assignment, and that’s where he found himself living at age 22-23. I don’t have to tell you that war is awful, but I do have to tell you that although he wasn’t in the worst area of combat, he did see some things that haunted him; and that he worked as a medic without any sort of formal training prior to his military service. And finally, I have to tell you that Agent Orange, the infamous chemical warfare that had been created to harm enemies, was being aerated throughout his environment. Eventually, my father was released of his duties to return home. Young 23 year-old Bill was reunited with his family when my oldest sister was 1, and went back to a job he’d secured at the IRS prior to the war. He and my mom continued creating their own family, and I came along, way ahead of schedule, after one failed attempt in-between. They went on to bring a total of six girls into the world over a 14-year span. As a child, I didn’t fully grasp the significance of this, or even my own significance, but I did enjoy all the babies being born into the family and the joy to my parents that came with each one. We were all deeply loved, wanted, and celebrated, and continue to be.

The author with her father celebrating his birthday.

My father worked his way up in the IRS, became a Special Agent, was sent from Cleveland to Cincinnati to work and eventually headed up the Criminal Investigation division of the IRS in Cincinnati. He did SWAT team duty and Secret Service detail when Presidents came to town. So here he is battling white collar, organized crime (yes, local mafia) and I swear to you, we as children did not know the level of risk he took and the danger he was in. We thought he was processing and reviewing people’s tax returns, looking out for dishonest folks, and making sure they followed the law; and we knew that that was a very important government job and were proud of our father’s work. It allowed mom to stay home with us for my and most of my sisters’ entire childhoods. Here’s what I noticed as a child: Dad left home in the morning and came home in the evening in a suit and tie, “dressed for success,” with a briefcase in his hand and a smile on his face. Sometimes he came home in different cars, but that was because they belonged to the government and they let him. And sometimes he traveled, but never very far, and never for very long. He was home to tuck us into bed most nights and we felt very, very safe. What went on in his job from 9–5 or 8–6 was no concern of ours. Our father was of great stature (6′ 6″) and strength; he boxed and exercised daily, he ate well, liked to do home improvement projects, read a lot, played a lot with us, was funny and silly, laughed until he cried sometimes, told the best stories, and kept his mind sharp; he was our very own super hero, built a lot like The Incredible Hulk, but looked more like Clark Kent minus the glasses. No one was getting past him. We slept well at night and he made sure of that. This went on for quite some time, just like this.

The author and her family enjoying a backyard pool one summer.

And then one day, my father fell off his bicycle while we were on a family vacation and it struck me as odd. His world and our world changed dramatically in mid-1997. The strongest man we knew personally was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. There was nothing that could be done to cure it, just some things to help with the symptoms: tremors, unsteady gait, freezing muscles, atrophied muscles, speech difficulty, lack of control over movement (the brain would know what he wanted to do, but the body couldn’t carry it out). And for whatever reason, he declined very rapidly in the first two years. Shocking both to him and us, and likely to them after 30 years of high-level work performance, he had to stop working at age 51 and he formally retired soon after from his position with the IRS. He had built up 9 months of sick leave never used. I have zero memories of my dad being ill for any noticeable period of time until he was ill with Parkinson’s Disease, for 17 and a half years. He lost weight, he was stuck in bed, he was distraught, he lost his sparkle, he lost who he was for a while, and that was easy to understand.

I was 24 when he was diagnosed in the late summer of 1997. I was starting my last semester of grad school for Clinical Psychology and knew some things about psychology, and maybe a small amount about life and death, joy and pain. I was about to get married. My parents chose not to tell us until after my wedding and after Christmas, my dad’s favorite holiday. My youngest sister was 12 at the time, the next sister was 14, and the third one, also still at home going to college, was 19. My other sisters were 23 and 27. One was living in D.C. practicing as a physician at Andrews Air Force Base; the other was an attorney. Mom and dad were both 50. It was devastating for all of us.

As most would guess and some have experienced, a major illness within a family typically qualifies as “traumatic.” Traumatic basically means there has been a threat to one’s life and one’s sense of safety and security. There is a sense of doom and gloom, of the unknown and the yet to be seen, but also the “I can’t believe what I’m seeing” aspect. There is an astonishment of the major changes that occur to the person with the disease. Thoughts like: “Their functioning is so deteriorated, will they be okay? Will they ever be the same again? Will they suffer a lot?” Within the patient, there is also: “I can’t believe what I’m feeling, this is very different” and “Who am I with this disease? I am not the same.” And for both the patient and the family: “HOW and WHY did this happen and what will happen next?” In terms of trauma, was having Parkinson’s Disease a threat to my father’s life? Yes, there was no cure and it’s a progressively debilitating disease. Was it a threat to his sense of safety and security? Yes. He could no longer rely on himself to protect himself from harm; he was also used to protecting others from harm and that was no longer possible the way it used to be. Try wrapping your head around that reality when your career and livelihood are made up of protection roles, not to mention your sense of self as a protector of your family, which he took very seriously. Was my father’s illness a threat to me? Yes, not physically, but in the sense of it meaning there was a threat to someone of major significance in my life, someone whose presence and well-being afforded me a sense of safety and security, even as an adult. My father was forced to look at himself differently, and I was too. And that was just plain sad and depressing for both of us. He told me tearfully one day, he couldn’t believe his “babies” had to help him get out of bed.

But then, about a year into the journey, a glimmer of hope appeared: his neurologist at UC told him about an experimental brain surgery that had gained some traction because Michael J. Fox had had it and it had been successful. Mom and Dad researched the information available on it and decided it was worth trying. Mom then had to fight the Insurance company for approval. Thankfully, she won that battle. In August 1999, my dad underwent deep brain stimulation surgery. The night before, we had a head shaving party for him and my husband, who had been balding since age 17 and sported a shaved head most of the time, did the honors. All of us were there to support dad, and I stayed for the surgery and days following. My two sisters closest in age to me lived out of state, and the three younger ones were still at home and had school obligations, plus they weren’t adults yet, this was not for them to do. I’ll never forget seeing him in the brain surgery “gear” that looked like a cage around his head with places where it was tightened with screws. To me, it looked like a crown of thorns, and I thought that was a pretty good representation of the suffering endured thus far, and the suffering I sensed would be endured before he got all the way through this chapter of his life. I shook the thought away and kissed him on the cheek and squeezed his hand before he went back. Something AMAZING happened that day! Surgery itself was successful and the intervention was wildly successful beyond what any of us imagined. Our dad started “coming back” and he was able to DANCE at my sister Sandi’s wedding in late September! He wanted to buy the shoes he rented with his tux for her wedding, he called them “magical shoes.” He hadn’t danced in 2 years and he was a great dancer, having taken ballroom dancing as a teen/young man. It was a glorious and hopeful time. We celebrated his increase in function with all of our family and friends. I celebrated it daily in my head. It went on for a good two years.

A pause here for one of dad’s favorite songs from his favorite movie, “Rocky.” It was his personal anthem and it became our anthem for his journey: “Eye of the Tiger” by Survivor and what a survivor he was!

The body and brain can do some amazing things, but there’s a bit of a time limit to all things. We are, in fact, only human. The decline started again. He was approved for surgery again, to have the deep brain stimulation done on the other side of his brain, in the hopes of a similar outcome. It didn’t take. It’s unclear why, but it was for sure a dashing of hope for all of us. But we moved on and forward. Mom and Dad had joined an extremely supportive Parkinson’s Disease group and were finding their people to talk with and share with. They could be spokespeople for the surgery, having been through it, and there’s nothing my mom likes more than helping others in any way she can. So there was “new life” there, and of course, we all continued on with our lives, reaching milestones such as graduations from high school, college, grad school, medical school, and the first grandbaby was brought into the family in early 2002: my daughter, Madilyn. We were living in Arizona at the time and came home in late 2002 as things worsened for dad. I didn’t want to raise my children without their grandparents anyway, nor did my husband. All the sisters who were living away at that time started making their way back home. My dad was still talking and able to be playful when Madilyn was an infant and into her first couple of years. The joy my dad had holding and interacting with her was priceless. We had made the right decision for sure. My older sister and her husband moved back at the same time we did with their daughter, who is just 6 months younger than mine. And my third sister soon got herself transferred to the closest air force base in Dayton, OH. No one was more than 2 1/2 hours away and we had family celebrations quite often, for holidays, graduations, weddings, and all the birthdays in our extended, growing family. Having everyone together was Dad’s favorite thing. By 2008, there were six grandchildren (4 girls and 2 boys) and five of the six of us were married. The babies’ presence always brightened up Dad and we brought them around as often as we could. We had all adjusted to the “new normal,” as much as anyone can. Dad was losing more capabilities and he and mom were living alone, empty-nesting for the past few years, as my youngest sister had been away at college more than she was at home. Mom went to work every day and Dad called her if he needed anything. She worked less than a mile away and could be home quickly. Then in March 2008, another major milestone in Dad’s illness, leading to another major change in his life (and ours) occurred. He was 60 going on 61 when he moved into a nursing home.

At that time, I had a 6 yr. old and a 1 1/2 yr. old. I was working in a community mental health center running an early childhood mental health initiative that had recently received a new grant. My husband was working late every night, kids were in daycare until almost 6pm by the time I picked them up, and we’d have some short, precious time at night after dinner and before bedtime to be together. My plate was full and I was emotionally and physically pretty well tapped. Then one morning, Mom called to let each of us know that she’d decided to put dad in a nursing home. She’d struggled with this decision, but couldn’t take care of him any longer at home without risking further injury to him or her. He had fallen again. She couldn’t pick him up, she had hurt her back doing that 2 years prior and had needed back surgery. She wanted him to have a chance at a longer life. He wanted to live longer, he was sure he could tough it out while the cure for Parkinson’s was found. He believed it was within reach. He believed in lots of things still despite his condition. At that point, Dad was low-functioning physically and was spending Mom’s work day at St. Charles Nursing Home where he could be attended to and socialize. He would be switched to full time care there.

It hit me like a ton of bricks, like a punch to the gut. I understood the reason, knew she’d kept him home too long, totally supported her decision, but still it STUNG. It stung like an actual bee sting in my heart and in my eyes, which filled with tears and turned into a sob as soon as I got off the phone. In my mind, this was “the beginning of the end.” Those exact words came out of my mouth to my husband and to a friend. Once Dad went into the nursing home full-time, he was on the path to death. He was 60 years and 9 months old, and that was just too early. Why didn’t he get a life to enjoy after retirement? Why did someone who worked so hard and did so much good for others get dealt this hand? It was too much sadness for me to bear and I knew it was way too much sadness for him too.

So Dad went into the nursing home to live, and that’s where he spent the remaining years of his life, at St. Charles, then at Rosedale Manor when St. Charles needed to make major building modifications. He didn’t want to be there, who does? In the beginning, he would plead with all of us girls to take him home, to go bring the car up and “break him out” of there. This usually happened when Mom wasn’t around. She was his security, his safe base. If she was out of town, which she only did a couple of times in the first year or two, he panicked. He was fully serious about being broken out and I wanted to laugh it off like he was joking, but I knew that was just me trying to set aside the pain of that reality. Within a couple of years, he had to be put permanently in a wheelchair so that he wouldn’t fall, another tick down the path. We all know what happens in nursing homes: there are more residents than the staff can handle, people get left alone, they wait long times for someone to help them because of short staffing and/or lots of needs from the residents. The staff do the best they can, but much like when babies are young and need 1:1 help, people with extremely deteriorated functioning often need and always do best with 1:1 help. In addition to increasing physical mobility issues, my dad had lost much of his ability to speak due to muscle deterioration in his mouth. This was a huge blow for him and for us when he couldn’t communicate well and it got harder and harder to pick up words and decipher sounds.

Mom knew the plight of nursing homes and she didn’t want him to be neglected, especially due to his communication and mobility issues. Her new routine, from day one of his admission, was: go to work in the morning, leave work at 5 and head to the nursing home, have dinner with dad every single night, then hang out with him, take care of him, and put him to bed every single night. Ok, she missed a grand total of like 10 nights in 7 1/2 years. But to me that’s still EVERY SINGLE NIGHT. When she needed something, she’d ask the staff for help. But she didn’t need much; she knew what he needed, that’s what happens after close to 40 years of marriage. So she more so befriended the staff and made them feel good about themselves, because that’s how she operates, the ultimate caregiver. It was in her blood and she truly enjoyed taking care of people. And she trusted the whole time that God had a plan, and that last piece is one of the main reasons that in 17 1/2 years, she never fell apart over this. The other piece that held her together was social and emotional support. And that has borne out in the scientific research of adverse experiences for many, many years. What I witnessed in her and in him inspired me and kept me from completely falling apart myself, but I did fall apart and get put back together many times with the help of others, including a couple different therapists over the years. And I adjusted, we all adjusted.

In early 2011, we finally figured out why and how Dad had Parkinson’s Disease. It had been a veritable Sherlock Holmes mystery trying to figure that out for the 14 years prior. Was it the pesticides Mom & Dad had used gardening all those years or some other toxic component in something else that was deemed safe then found later not to be safe, was there a genetic component yet unfounded, was he just unlucky like people who get cancer out of nowhere? The answers to all of those questions were: “it could be.” I’ll never forget the night my physician sister who was still in the military told us a report had come out from the government letting people know that Agent Orange had been found to be tied to a list of 27 neurological diseases, 27, you bet I counted, and guess what one of them was. I was relieved for about 5 minutes, we finally knew! Then I was angry, very angry at that decision made by someone (or ones) to expose their own people to debilitating chemical warfare. They knew what they were doing, it was meant to adversely affect the enemy in the war. How could they not know it would also affect the soldiers? So they took some responsibility to make it right 40 years later. Gee thanks, that’s great of you. My father is dying after sacrificing his life for his country and being exposed to terrible things in the war, then working 30 years for the same government that, in my mind, betrayed him. And it wasn’t just him with this life sentence. I shuddered to think of all the families that felt the same. I went to D.C. with my family in 2014 and wouldn’t visit the Vietnam memorial. It was too much for my empathic self.

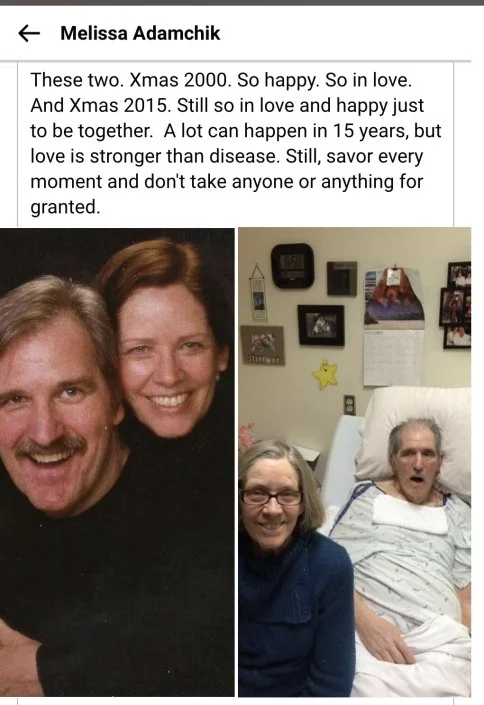

Speaking of frustration and anger, one of the most interesting and perhaps one of the most awe-inspiring things that I learned during my dad’s illness was that strong emotions can supersede depleted functioning. I saw both ends of the spectrum. The smile he usually couldn’t make with his mouth and facial muscles, would actually appear when someone made him laugh or when the grandbabies came around. And when he was angry, the words somehow formed in a way they usually couldn’t. It was like a light in the darkness. I was happy for that anger. I didn’t want him to be angry, but I wanted him to function better and for those moments, he absolutely could! And then I saw the best thing of all during this prolonged time of overall sadness that was his disease; I saw how the love of my mother sustained him and how his love for her and us sustained him. How did he stay alive for 17 1/2 years when one year into his diagnosis, he had gone all the way to an advanced state of the disease? How did he survive 7 1/2 years in the nursing home? LOVE. And mostly their love. I had witnessed the power of true love first hand, the kind that’s in wedding vows and in fairy tales, the kind that doesn’t change even when your loved one drastically changes, the kind that allows a weak, dying man to squeeze a hand and to form a kiss with his lips to kiss his wife, his children, and his grandchildren. I discovered how love heals and how it lights the darkness.

The scary, frequent hospital visits started in 2011 and thus in 2011, 2012, 2013, and especially in 2014, time seemed to be marked by those hospital visits. My father’s body was continuing to break down, to follow the proper trajectory of the disease. The dopamine that used to run like a waterfall when he was young, slowed to a trickle, and this affected various organs and body systems, thus affecting his functioning in significant ways. He fought so hard during those years to keep afloat. What do you do when your own body is the opponent in the ring? Some days, you let it win because you’re tired and worn and the medication cocktail is too sedating. And some days, you muster up some gumption and say, “I got it. I won’t let this disease take me down.” I wouldn’t have blamed him for doing the first option most days. But it wasn’t often that he gave up or submitted to the body’s troubles. That wasn’t in his blood. As much as my mom was a caregiver in her core, my dad was a fighter in his core.

Dad would go to the hospital and just when we thought he was slipping away, he’d gather some of his strength back. The hospital experiences were terrible for all of us, and especially Dad. He wanted to be there even less than he did the nursing home. For me, it was an emotional roller coaster and I’d go into a heightened mode of stress and vigilance quite frequently. I always wore my emotions on my sleeve and it was easy to see I was affected. Sometimes I’d fight by gathering more information and pushing for things that might help dad more; sometimes I’d flee by taking long drives; and sometimes I’d freeze for a bit with overwhelm; always I flocked to my mom and sisters so we could support each other. Those frequent hospital visits did afford me and my sisters opportunities to support dad in ways we never thought about when we were younger. He had a care team of his wife and six other women now, and this included a lawyer, a psychological practitioner (me), a doctor, a teacher, a social worker, and an insurance agent. I was so happy to serve him in this way with my psychological expertise and my understanding of trauma and sensory issues. I had a sixth sense for his suffering and what he needed. I’m not entirely sure how, but I’ll call it a gift. There were many times I happened to call my mother when they were headed to the hospital. And because I had been given that gift of sensing it, I knew I needed to be there. My sisters and I would all show up at different times at the hospital and do our things. One time, I had to tell the nursing staff that Dad was having a panic attack; I also saw him be triggered by various things; he wasn’t being non-compliant, he was reacting to something that felt dangerous. Several times, I rubbed his feet for some soothing touch & relief (he loved it), and I remember how he let out sighs of relief and noises of content when we washed his hair in a special cap that had the shampoo in it. When your body is causing you mostly discontent, you relish those times when body experiences can be taken in the opposite direction. My sister the doctor kept an eye on the medications they gave him in the hospital, told my mom when one wasn’t a good idea, and asked informed medical questions. My sister the lawyer made sure mom had all the living will and regular will pieces put together. She advised on all things legal. My 1st grade teacher sister and my social worker sister were warm and gentle like you are when you spend lots of time with children; all of us were, we’d been taught well to care for others. The social worker sister was also a good advocate, right alongside mom. Remember how my youngest sister was 13 when my dad got diagnosed and still lived at home for many years into his illness? She and my mom developed a very close bond because they had been through a lot of the trauma together. She had that sixth sense about my mom that I had for my dad, and still does. She knows when mom needs something and alerts the rest of us. People have told me how fortunate my dad was to have my mom and all of us to help him during his illness. And I feel we wouldn’t have been good at it had he and my mom not raised us well. I am aware daily how fortunate I am to have had my father and mother as parents. The next piece of the story will undoubtedly demonstrate that.

In July 2014, my son Myles turned 8 and we had a birthday party at the pool in our neighborhood. Mom brought Dad in his wheelchair. He still came to all the parties, even if he was tired. And this time, as he sat in his wheelchair watching the kids swim and jump into the pool, he managed to eek out of his shallow voice, “I just want to walk again.” That was his wish on my son’s birthday, to get up and walk, after about 7 years confined to a wheelchair. His wish was barely perceptible to my mom and my sister who were right next to him, and they more or less said, “Oh, you want to walk? Okay, let’s do it, let’s get that figured out.” This is how we approach challenges as a family. Not “that’s a terrible idea that will not work and be way too dangerous,” rather “okay, let’s figure that out.” I can’t tell you how many times that philosophy has come in handy in my work and my life. My son’s birthday is July 5th and although I don’t remember the date of his party that year, I do remember the day my dad walked again: July 28, 2014. I also distinctly remember the day he stood up again for the first time because I was on the beach in Florida for a family vacation and mom sent photos and video. That was July 14. So what we have here is a seemingly impossible wish spoken in early July that was fulfilled within the space of less than 30 days. Say what?? And how in the world did this feat—and we are truly talking medical miracle here—get accomplished? The power of the human spirit, the power of faith, the power of love, and the power of support.

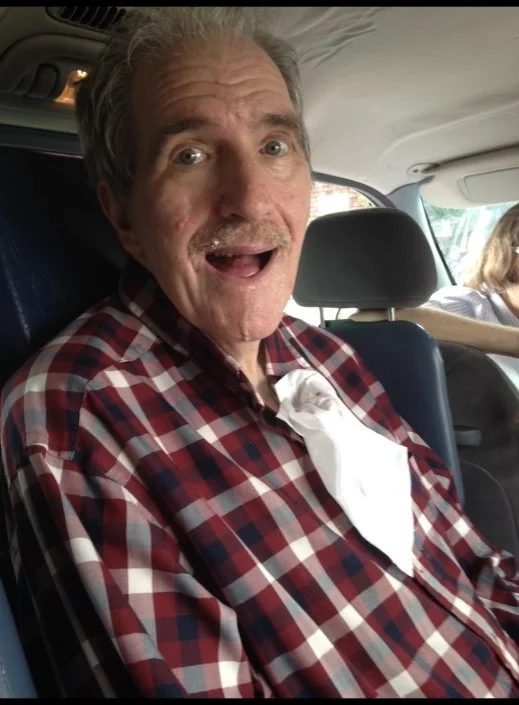

My mom took my dad to Dairy Queen to celebrate. This is him showing his pride and elation, as best he could with his facial muscles being what they were at that time. This, my friends, is what triumph over trauma looks like. This is precisely why my father remained my hero through his illness. This is how he earned the title trauma warrior.

Enter another person who believes in the power of all those things: the new physical therapist at Dad’s nursing home. A young, strong, bright-eyed, faith-filled man. Also know that my mother’s job had been suddenly eliminated one month prior to where she could spend many more hours a day at the nursing home supporting and caring for my father. Then realize that all the necessary pieces for a miracle to occur have been put into place: my dad’s fighting spirit and strong will; the faith of my dad, my mom, we his children, and his physical therapist; the support of all the people around him cheering him on; and the love I talked about between my parents. Then you will see how a man whose muscles have atrophied extensively, whose body doesn’t know how to support itself anymore, and whose ability to walk in a forward fashion was stymied many years ago by the reduction of dopamine in his brain CAN FULFILL HIS WISH of walking again. I still get chills thinking about it. If you could have seen the video, you’d have chills too. If you could have seen him walking at different times for the next couple of months, you’d have been witness to this amazing feat and probably called it a miracle too. When we told everyone we knew, they celebrated with us and with him. We were as elated, if not more so, as the time after his first brain surgery, because this wasn’t a scientific or medical procedure that produced this. This was will, this was faith, this was love and support. This was divine intervention and this created hope. My mother later said, “God worked a miracle through Dad and the timing was perfect; we all needed it to happen before his death.”

This next part is by far the hardest to relive and relate. Thus, I ask for your grace, if it seems less fluid than the rest of the story. After he walked again, my father lived about 6 more months. He caught a virus in September that year and it was strong enough to put him in the hospital. He wasn’t in continuously, but from that point he was in and out a lot. His body couldn’t successfully fight it; he was too worn down by the cumulative effect of his disease. We had gone from a super high with the walking to a super low, as the reality of him “not making it” set in. It was a bit of an emotional roller coaster, to say the least: sadness, hope, sadness, hope; stress, relief, stress, relief, stress; so many stays at the hospital with the problems only partially solved, if at all. Dad was weak, he couldn’t communicate verbally, he was just hanging on, hoping to make it through again. When one hospital wasn’t doing enough to help him, we transferred him elsewhere.

Thanksgiving with family didn’t happen that year. Mom was at the hospital with Dad. I honestly don’t remember what I did with my family unit. It didn’t matter. I was on autopilot, going to work, hitting the hospital or the nursing home on my way home. One night, about 4 days before Christmas, we conspired to take Dad to UC’s Emergency Room. My sister was sure they’d do a good job helping him. He only stayed about 24 hours. They told my mom that it was time to move towards preparing for his death, to get hospice or some other palliative care program involved. There was nothing they could do. They, in fact, told her she needed to “let go,” that her expectations of Dad improving were unrealistic at this point. Ouch. It was like telling someone to give up hope. Dad was transported back to his nursing home, and we all met with the hospice representative on Christmas Eve while Dad lay in his bed, very weak and unable to participate. He looked terrible. I know I held back tears, and my sisters likely did too. We made plans to have our Christmas there at the nursing home, bring all the kids and the presents; it would be his last. All of our children had been around a lot, they knew Pa was in bad shape. They’d been drawing him pictures and giving him hugs and listening to us tell stories, as we sat in his room around him.

And God love him, knowing it would be his last Christmas, and Christmas being his favorite holiday, one where he always played Santa, giving out presents from under the tree, wearing his Santa hat, Dad conjured up enough strength to get out of bed. We were all very grateful and joyful that day. And on New Year’s Day, a week later, he was sitting up in bed laughing with some good friends there to visit him for the last time. And we all thought, maybe the doctor was wrong, maybe he’d be okay, maybe he’d pull through again. But he wasn’t being treated for anything at that point and wouldn’t be. The goal was comfort, taking in what food he could, seeing how things went. On January 5, he stopped eating and drinking, no strength to even do that. He was resting, resting in a way that he hadn’t for 17 and a half years.

I think I was there every day after that. I didn’t want Mom to be alone when he passed, and I wanted him to know that he was deeply loved and not alone either. And for all the times he had been there for me, had protected and supported me, I owed him at least my presence in his final days. It was hard as hell to watch him slowly die those last eleven days of his life. It was gut wrenching, when I slept the little I slept those days, I would wake up wondering if he’d passed, but then realized Mom hadn’t called, so he must still be hanging on. And I thought of what else I needed to say to him, and there wasn’t anything else. It was just, “I love you, Dad, and I’m here for you” on repeat every day. It was holding his hand, gently touching his head, or his shoulder, or his arm, kissing him hello and goodbye, fighting the same sort of tears I have now writing this, until I left and got in my car. He didn’t need my tears. He needed my love and my calm, nurturing presence which I knew how to keep in tact after 17 years of being a therapist. Maybe I had been given all the skills I needed for moments like these. Maybe it was meant to be that Mom and Dad had raised a treatment team of women to help, to be all the things needed in dealing with a long term, debilitating illness and death. I took some comfort in that.

Dad passed peacefully on the morning of Friday, January 16, 2015, around 10am. Mom was there, but none of us girls. I was on my way and another sister had recently left. Mom said she was sure Dad didn’t want any of us to see him die, even though it wasn’t anything he could verbalize. The rest of my sisters were called to come and we hugged and cried and gave dad one last kiss goodbye. His 17.5 years of struggle had come to an end and we were grateful for that, for him to be at peace. We managed to pull off a funeral three days later on Martin Luther King Day. It was beautiful and there were so many people there to pay their respects. Some that my sisters and I had never met came to tell us about how our father touched their lives. And others who we did know, told us things that he had done to help or touch them too. He had made his work colleagues feel safe and protected; he had inspired neighbors with his fighting spirit throughout his whole illness; he had told such great ghost stories when our childhood friends spent the night; he had been a wonderful friend, brother-in-law, uncle, son, brother, supervisor, colleague, neighbor, and resident at the nursing home. Of course he had been, I knew the type of person he was, but it was incredibly touching nonetheless.

My father has left a legacy that continues to grow. He has 14 beautiful and amazing grandchildren, ages 1-20, 7 girls and 7 boys. He always wanted more boys in the family and after his death, 4 of those 7 boys were born, two almost on his birthday. I feel his presence often, I feel his guidance and influence in a way I never would have anticipated. And I am grateful every day that I am his daughter.

Thank you for hearing his story.